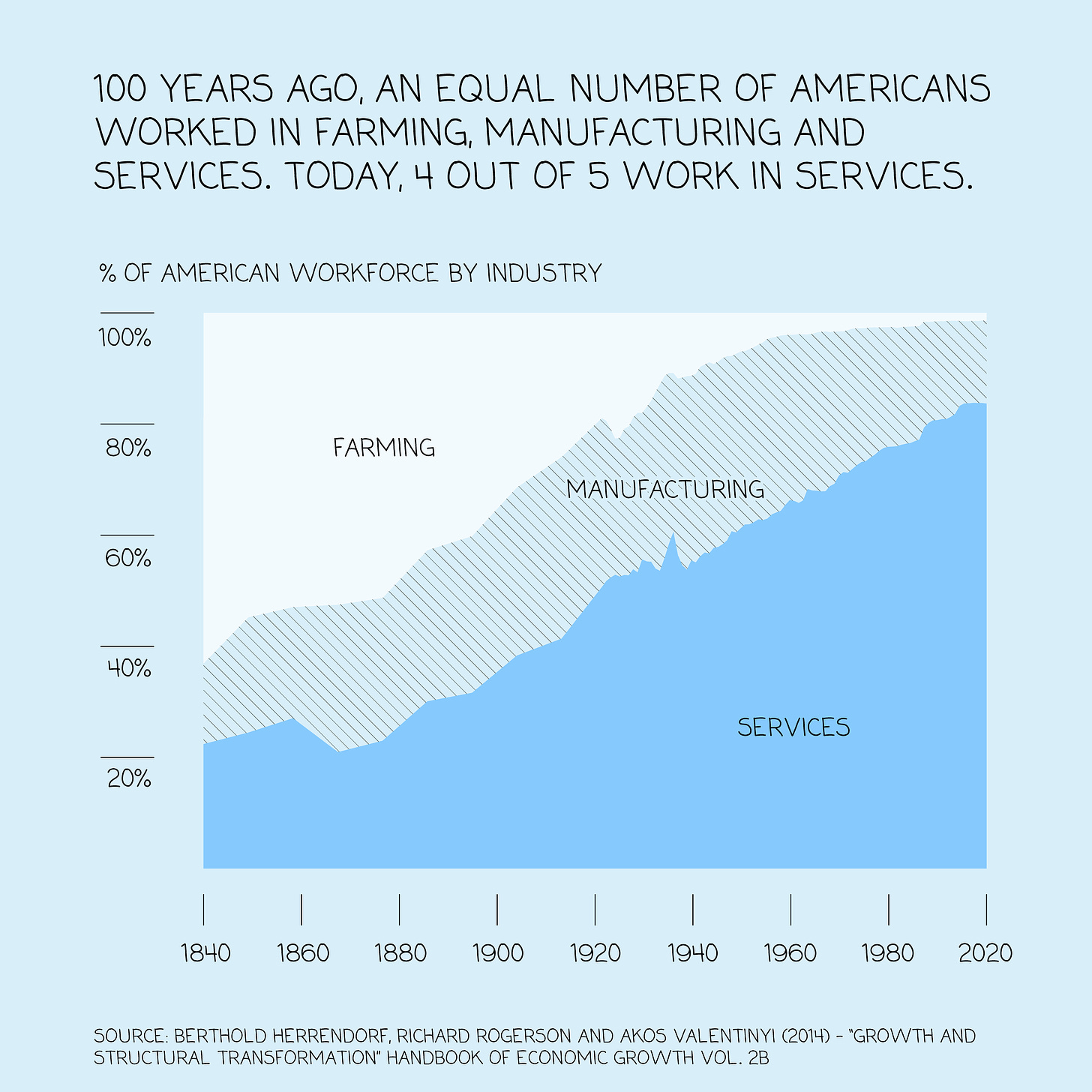

The changing structure of the US workforce

The transition to services explains so much about our world today

Toilet computer

Here is an admittedly gross (but hopefully relatable, to some of you) admission: I’ve been taking my iPhone—aka the toilet computer—into the bathroom with me every morning for years. Doing my business takes just enough time to allow me to check emails and glance at the New York Times headlines (and scroll through Instagram or Twitter for …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Home Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.